- This event has passed.

Art/Race/Violence: A Collaborative Response

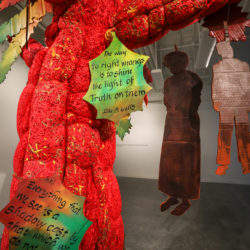

Organized by Dr. Earnestine Jenkins and Richard A. Lou (from the University of Memphis) in collaboration with Crosstown Arts

Gallery Hours:

Monday-Friday 10 am-8 pm

Saturday 10 am-6 pm

Sunday noon-6 pm

Featuring work by artist teams:

Jamin Carter and Mary Jo Karimnia (with Special Design Work for American Heritage Lotto by Christian Westphal)

Andrea Morales and Terry Lynn

Lisa Williamson and Lurlynn Franklin

Yancy Villa-Calvo and Lawrence Matthews

Jamond Bullock and Cat Pena (video work by local artist Perry Kirkland and survivor profiles from #SurvivedAndPunished)

Karina Alvarez and Carl Moore

Jin Powell and Jesse Butcher

Agustin Diaz, Brittney Bullock and Brenda Joysmith

Opening reception will feature a curator talk at 3 pm followed by spoken word performances from Janay Kelly, Nadifah Rasheed, Tray Butler, Roberto Alfaro, and Jessica Taylor.

More events:

Art/Race/Violence: Artist+Community Conversation

Wednesday, Nov 29, 12-1 pm

Galleries

Conversation with artist teams Jamin Carter and Mary Jo Karimnia and Terry Lynn and Andrea Morales, led by Ladrica Menson-Furr and Richard Lou.

Art/Race/Violence: Artist+Community Conversation

Thursday, Dec 7, 12-1 pm

Galleries

Conversation with artist teams Yancy Villa-Calvo and Lawrence Matthews, Cat Pena and Jamond Bullock, led by Tami Sawyer.

Art/Race/Violence: Panel Discussion

Thursday, January 11, 6-8 pm

Theater Stair

Speakers as of November 7: Shahidah Jones, Antonio De Velasco, Tom Carlson

“There has never been a free people, a free country, a real democracy on the face of this Earth. In a city of some 300,000 slaves and 90,000 so called free men, Plato sat down and praised freedom in exquisitely elegant phrases.” -Lerone Bennett Jr.

“We are equidistant from utopia and Armageddon.” -Guillermo Gomez-Pena

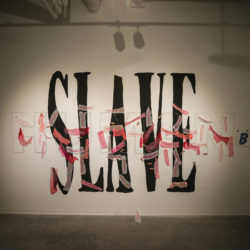

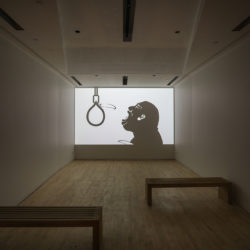

Art/Race/Violence: A Collaborative Response is a multidisciplinary project organized by visual culture historian Dr. Earnestine Jenkins and artist Richard Lou in collaboration with Crosstown Arts. Through this project, local artists collectively explore intersections of race and systemic violence through the lens of cultural expression. Conceived to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Ell Persons’ very public murder by members of the Memphis community through the act of lynching, the project was further inspired by recent events to memorialize lynching sites in the broader Memphis community in an effort to bring about greater understanding of racial oppression and violence in the South.

The organizers aim for more challenging, candid and unvarnished representations of our city’s history through a range of educational programming, including panel discussions which began last spring, a collaborative exhibition (with performances and talks by the artists) opening this November, community conversations, and film screenings. On March 16th of 2017, the University of Memphis Art History and African-American Studies programs jointly hosted “Ida B. Wells: A Blues Woman.” Panelists Earnestine Jenkins, George Lipsitz, and Celeste Bernier looked at Ida B. Wells and the beginnings of resistance to lynching within the context of the late 19th century, linking it to modern social movements. Panelists addressed how the arts are linked to the culture of resistance, as Ida B. Wells was the first strategist to use visual images, specifically lynching photographs, as proof of the racial violence so endemic to the South.

Much as Wells did a century ago, the artists and cultural workers involved in this exhibition were invited to reflect upon the nature of Memphis’ past and present and use their creative work as a social instrument for change. One of the distinctive components of this collaborative process began with the curators selecting artist teams to conceive of and co-create new work to share with the public. The participants attended a series of workshops and panel discussions and were given access to a wide array of resources, articles, and media for their research. The artist teams — Jamin Carter and Mary Jo Karimnia; Andrea Morales and Terry Lynn; Lisa Williamson and Lurlynn Franklin; Yancy Villa and Lawrence Matthews; Jamond Bullock and Cat Pena; Karina Alvarez and Carl Moore; Jin Powell and Jesse Butcher; and Agustin Diaz, Brittney Bullock and Brenda Joysmith — have created 8 new installations in a range of media, including video, sound, sculpture, and performance, which will be on view in Crosstown Arts’ new galleries at Crosstown Concourse.

In Martha Stoudt’s book, The Sociopath Next Door, she states that it is natural for individuals to question their moral compass when surrounded by unethical attitudes and behaviors; the notion of “if you can’t beat them, join them” is an understandable inclination. However, Stoudt counters that when faced with that lack of consciousness, we do not need less consciousness; we need more. As artists, the search to make work that matters carries a greater significance since the last U.S. Presidential election cycle. The spectre of a divided nation (an inequality that marginalized and subjugated communities living in the U.S. are intimately familiar with and have endured for centuries) has re-inserted itself into the current national public discourse. The idea that there are large segments of the U.S. population, living side by side, in parallel universes — the haves and the have-nots, the subjected and the privileged — has become the rule, not the exception, in how we now imagine ourselves as citizens of the United States. Participating artists in this project are challenged to create work that speaks to and crosses these divides.

Art/Race/Violence: A Collaborative Response will utilize the arts across diverse disciplines, media, and varied forms of cultural expression. The exhibition will challenge artists to use diverse media to reclaim cultural expression of humankind’s (or “this country’s”) history of racially motivated violence, as well to examine this history from multiple viewpoints. The project is designed to call on artists to reflect upon the nature of our past and present day in Memphis and to think of their creative work as a social instrument, or as Estella Conwill Majozo stated, “To search for the good and make it matter.”

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Compiled by Dr. Earnestine Jenkins

Lynching, the collective, systematic terrorism directed mostly toward African Americans by white mobs, arose following Reconstruction and persisted well into the 20th century. Most lynchings in Tennessee occurred in the western and middle parts of the state. Lynchings are documented in 70 Tennessee counties with Shelby County ranking first. According to Margaret Vandiver in Lethal Punishment: Lynchings and Legal Executions in the South, there were at least 15 lynchings in Shelby County. Ninety-nine percent of lynchers in the U.S. escaped arrest and punishment. Memphis is particularly significant in reference to two high-profile executions that attracted national attention and propelled individuals and organizations to act.

People’s Grocery Lynching & Ida B. Wells

In March of 1892, black business owner Thomas Moss and his employees, Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart, were arrested for defending themselves against an attack on their store, People’s Grocery, in an area just outside Memphis. The three were defending themselves from police officers and the white owner of a neighboring grocery. In the fray, several deputies were wounded but survived.

Moss, McDowell, and Stewart were booked into the downtown jail, but they were later pulled from the jail by a white mob. The three were dragged to a deserted rail yard in North Memphis and shot to death.

The murder of the young men enraged journalist Ida B. Wells, and this incident became a turning point in her life. She began traveling the south to investigate reports of white violence against blacks. She found middle-class black people were just as subject to murder by whites as poor blacks were. Wells discovered that black men were often being lynched not for rape but as punishment for having sexual relations with consenting white women. Wells asserted that the real reason for lynching was in retribution to black economic progress. She first published her findings in an 1892 pamphlet entitled “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.”

“Nobody in this section of the community believes that old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women. If Southern men are not careful, a conclusion might be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women,” wrote Wells.

In retaliation, Wells’ life was threatened in Memphis newspaper articles, the writers of which assumed she was a man. The Memphis Scimitar issued this warning: “It will be the duty of those whom he has attacked to tie the wretch to a stake, brand him in the forehead with a hot iron, and perform upon him a surgical operation with a pair of shears.”

White males destroyed Wells’ newspaper, which was housed in an office on historic Beale Street. Wells was out of town at the time, and she chose not to return. She went on to launch a national crusade against lynching in the U.S. and abroad.

The Ell Persons Lynching & the NAACP in Memphis

Ell Persons, accused of raping and murdering a 16-year-old white girl named Antoinette Rappel, was burned alive near the Macon Road Bridge at the Wolf River on May 22nd, 1917. Drawn by headlines in The Commercial Appeal, several thousand men, women, and children showed up to watch as Persons was decapitated, dismembered, and had his heart cut out. Rappel’s mother declared, “Let the Negro suffer as my little girl suffered, only 10 times worse.” The mob enjoyed the spectacle as they chewed gum, ate sandwiches, and enjoyed soft drinks.

Person’s head was later thrown into a crowd of African Americans on Beale Street. No one was ever charged with the crime. Persons’ death was one of the most vicious lynchings in American history. After the event, horrified African Americans in Memphis gathered to express their pain. When NAACP Field Secretary James Weldon Johnson arrived in Memphis to investigate the lynching, Robert R. Church, Jr. brought him to this site where an American flag marked the charred and blackened earth. Johnson found no evidence that Persons killed Rappel. He wrote that “the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.”

Johnson found a black community ready to take a stand in combating daily racism and violence in the South. With the help of Robert Church, Jr. and businessman Bert Roddy, the Memphis branch of the NAACP was organized with 53 members. It was the first NAACP branch in Tennessee and only the fourth branch in the South. The next year, when Johnson made his tour of NAACP branches, he returned to speak on April 14th to an audience of about 2,500 people crowded into Church Park and Auditorium. The meeting launched a vigorous campaign, growing the membership to 924.

Robert Church Jr. publicly denounced lynching and endorsed the work of the NAACP when it was dangerous to do so. At the first Lincoln Republican League meeting at Church Auditorium following the Ell Persons atrocity, Church spoke to over 3,000 people, proclaiming “I would be untrue to you as your elected leader if I should remain silent against shame and crime of lawlessness of any character, and I could not if I would hold my peace against the lynching or burning of a human being …”

By 1919, the Memphis NAACP was the largest branch in the South. Robert Church, Jr. was the first Southerner elected to the NAACP’s National Board of Directors, helping to launch 68 branches in 14 states. Together, the lynching of Ell Persons and the establishment of the Memphis NAACP in 1917 changed the political landscape of the South.